Kikonge and the question we keep avoiding: Who really benefits from Zambia’s minerals?

By

Prof Cephas Lumina

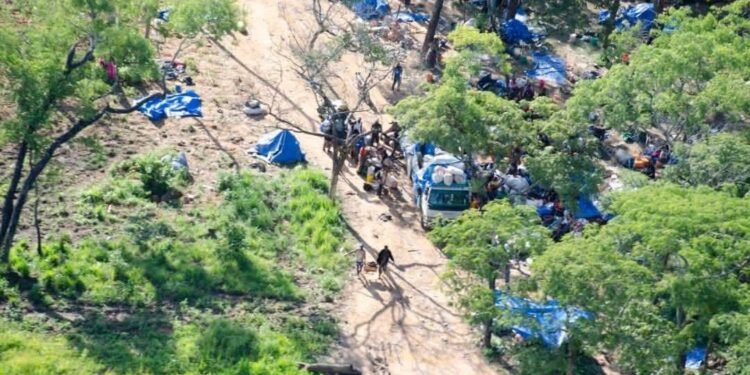

OVER the past week, national attention has been gripped by the controversial remarks attributed to Zambia Army Commander, Lieutenant-General Geoffrey Zyeele, regarding plans to forcibly remove illegal miners from the Kikonge Gold Mine in Mufumbwe District. As has become increasingly common in debates on matters of national importance, public discussion has hardened along partisan lines.

Some have framed the issue as a necessary assertion of State authority, others as an abuse of power or a sign of elite capture. Lost in the noise, however, is a more fundamental question: what happens next after the illegal miners have been removed?

The government has since announced that the operation has been successfully concluded. State House Chief Communications Specialist, Clayson Hamasaka, reportedly described the clampdown as a decisive measure to ensure that Zambia’s mineral wealth benefits all Zambians (Thandizo Banda, “Illegal mining clampdown elates State House,” The Mast, 27 January 2026). On this point, there is broad agreement. Few citizens would dispute that minerals should contribute to national development, improved living standards, and poverty reduction. The challenge lies not in the stated objective, but in how that objective is pursued, grounded, and sustained within the framework of the Constitution.

The Kikonge Gold Mine, like many mineral projects before it, presents a test of whether the country can move beyond a familiar cycle in which resource wealth generates conflict, opacity, and disappointment rather than shared prosperity. Removing illegal miners may restore order in the short term, but it does not answer the deeper questions of ownership, benefit-sharing, public participation, and constitutional accountability.

A constitutional lens we cannot avoid

Our Constitution does not treat economic policy as a purely technocratic exercise. Article 8 sets out national values and principles that must guide the development and implementation of State policy, including human dignity, equity, social justice, equality, non-discrimination, good governance, integrity, and sustainable development. These are not aspirational slogans. They are binding constitutional standards.

Article 10(2) obliges the State to promote the economic empowerment of citizens so that they may contribute meaningfully to sustainable economic growth and social development. Article 90 provides that executive authority derives from the people of Zambia and must “be exercised in a manner compatible with the principles of social justice and for the people’s well-being and benefit.” Article 225(f) is unequivocal that benefits accruing from the exploitation and utilisation of environmental and natural resources must “be shared equitably among the people of Zambia.” Articles 255(i) and 257(d) reinforce this framework by requiring effective public participation in the development of policies, plans, and programmes, and by mandating the State to encourage public participation in the utilisation of natural resources.

Any serious discussion of Kikonge must therefore begin not with personalities or partisan loyalties, but with constitutional obligations. The Constitution demands that mineral governance be transparent, participatory, and oriented toward the public good.

Who owns Kikonge, and why it matters

It is critical for the public to know who owns Kikonge Gold Mine and what the government’s concrete plans are to ensure that benefits from the mine accrue to the people of Zambia. Silence or vagueness on ownership fuels suspicion, undermines trust, and invites misinformation.

In this regard, an important but under-discussed development is the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed in December 2025 between the Ministry of Mines and Minerals Development, ZCCM-Investment Holdings (ZCCM-IH), and Mining Mineral Resources-SAS (MMR), a private mining firm based in Lubumbashi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. MMR is part of the Vinmart Group, which operates globally in critical mineral supply chains.

The MoU indicates a transition from a chaotic gold rush to a regulated industrial mining project. It establishes a joint venture in which ZCCM-IH holds a 51 per cent controlling interest, while MMR holds 49 per cent. MMR is responsible for providing technical expertise and capital investment to establish mechanised mining operations and modern processing facilities. ZCCM-IH is designated as the sole off taker of all gold produced, ensuring that proceeds remain within the national financial system and contribute to national reserves.

The agreement also commits the joint venture to infrastructure development, including roads, schools, and health centres, as part of a formal social responsibility plan. On paper, these arrangements align with the Constitution’s requirement that benefits from natural resources be shared equitably and contribute to national development.

What about the artisanal miners?

Perhaps the most sensitive aspect of the Kikonge situation concerns artisanal and small-scale miners. Their sudden removal raises legitimate fears of displacement, loss of livelihoods, and social unrest. The MoU outlines a proposed “formalisation” model intended to integrate artisanal miners into the legal economy rather than exclude them.

Under this model, the Ministry of Mines and Minerals Development would organise individual miners into registered cooperatives granted legal access to designated zones within the mining tenement. The joint venture would provide training in safer mining techniques and access to small-scale equipment, replacing the dangerous hand-dug tunnels that have previously resulted in fatalities.

Artisanal miners would gain a guaranteed legal market for their gold at fair prices through linkage to the joint venture, reducing dependence on smugglers and foreign middlemen. Environmental standards, including controls on mercury use, would also be enforced.

If implemented transparently and in good faith, this approach could advance the constitutional values of dignity, equity, and social justice. If mishandled, it risks becoming another unfulfilled promise to communities already living on the margins.

Minerals as a public trust

Under the country’s mining laws, all minerals are vested in the President on behalf of the Republic. This formulation is often misunderstood. It does not mean that the Executive owns the minerals in a proprietary sense. Rather, it reflects a trust relationship: the State holds mineral wealth on behalf of the people of Zambia.

This trust principle is foundational. It means that when mining rights are granted, transferred, or regulated, the Executive is exercising authority delegated by the people. That authority must be exercised lawfully, transparently, and in the public interest. Decisions taken behind closed doors, without adequate disclosure or participation, undermine not only good governance but the constitutional trust upon which executive authority rests.

This obligation is reinforced by Article 90 of the Constitution, which requires executive authority to be exercised for the people’s well-being and benefit. Decisions concerning mineral resources therefore cannot be justified solely by reference to legality or expediency. They must demonstrably advance the social and economic interests of the people in whose name executive power is exercised. Where mineral governance yields exclusion, opacity, or inequitable outcomes, the Executive risks acting inconsistently with the constitutional basis of its authority.

The constitutional case for a comprehensive mineral audit

If mineral resources are held by the State in trust for the people, transparency regarding those resources is not optional. It is a constitutional obligation. A trust cannot be properly administered where citizens lack reliable information about what mineral assets exist, who controls them, the terms on which they are exploited, and the benefits that accrue to the public.

There is therefore a strong constitutional basis for a comprehensive, independent audit of the mineral sector. Such an audit should cover mineral reserves, licensing and beneficial ownership, production and trading arrangements, fiscal terms, and revenues received by the State. Without this baseline of verified information, mineral governance operates in opacity, weakening accountability and public confidence.

Articles 8, 90, and 225(f) of the Constitution collectively require that mineral wealth be managed in a manner that is transparent, accountable, and equitable. These obligations cannot be meaningfully realised in the absence of clear, accessible information about how mineral resources are managed and monetised.

A comprehensive audit would provide a constitutionally sound basis for mining policy. It would support meaningful public participation, as required by Articles 255(i) and 257(d), and ensure that policy choices are grounded in evidence rather than assumption or selective disclosure. Properly conceived, such transparency would improve legal certainty, reduce conflict, and strengthen the legitimacy and sustainability of the sector.

Kikonge as a symptom, not an exception

The controversy surrounding Kikonge should not be dismissed as an isolated incident. It reflects recurring weaknesses in mining governance in the country, including unclear beneficial ownership, opaque licensing processes, and insufficient community engagement. These conditions create fertile ground for conflict, political controversy, and litigation.

Where systems are transparent, rules are consistently applied, and communities understand who holds rights and on what terms, such disputes are far less likely to arise. Kikonge is therefore not just a gold mine. It is a mirror reflecting broader structural challenges in how the country manages its mineral wealth.

The link between minerals and the national debt

The country’s mineral wealth is often invoked in abstract terms, yet the lived reality is stark. Despite mineral exports generating more than US$10 billion annually, the country continues to carry an external public debt burden estimated at between US$21 and US$24 billion, even after restructuring efforts.

This contrast should concern us. A country that earns billions each year from mineral exports should not perpetually struggle to finance basic public services or rely on repeated external borrowing to meet fiscal obligations. The problem is not a lack of mineral wealth, but the chronic failure to capture a fair and just share of that wealth for public benefit.

Revenue leakage in the mining sector occurs through under-declaration of production, aggressive transfer pricing, profit shifting, opaque trading arrangements, overly-generous tax incentives, and weak enforcement capacity. Illicit financial outflows from mining—whether through mispricing, offshore trading hubs, or complex corporate structures—further erode the tax base. The result is that while minerals leave the ground in vast quantities, the public revenue that should follow them does not materialise.

This is where tax justice becomes key. Appropriate taxation of mining companies—applied consistently, transparently, and in line with the law—is not anti-investment. It is a constitutional and developmental necessity. When mining companies pay what is lawfully due, the State gains the fiscal space to reduce dependence on external borrowing, service existing debt, and invest in infrastructure and essential public services.

Robust measures to stem illicit financial outflows from the mining sector would have transformative effects. Even modest improvements in tax compliance and revenue capture could translate into billions of kwacha for hospitals, schools, water and sanitation projects, energy infrastructure, and social protection. These are not abstract benefits. They directly affect human dignity, equality, and social justice—the very values enshrined in Article 8 of the Constitution.

Debt, in this sense, is not an unavoidable misfortune. It is a policy outcome. Every dollar lost through tax avoidance or illicit outflows is a dollar replaced by borrowing, contributing to an unsustainable debt burden carried by ordinary citizens. Conversely, every dollar recovered through fair taxation and effective enforcement is a step toward fiscal sovereignty, developmental autonomy, and the upliftment of citizens.

From policing to policy

The removal of illegal miners may have been necessary to restore order and safety. But policing is not policy. The constitutional test lies in what follows.

Will government clearly disclose ownership structures and contractual terms? Will affected communities and artisanal miners be meaningfully involved in shaping the future of the project? Will revenues be transparently accounted for and linked to visible public benefits?

The answers to these questions will determine whether Kikonge becomes a symbol of reform or another chapter in a familiar story.

A constitutional moment

Kikonge presents the country with a constitutional moment. It offers an opportunity to demonstrate that mineral wealth is governed not by force or expediency, but by law, participation, and accountability. It is a chance to show that the values in Article 8 are operational rather than rhetorical, and that Article 90’s requirement of people-centred executive authority is taken seriously.

Managed properly, Kikonge could signal a renewed seriousness about linking resource wealth to development and dignity. Managed poorly, it will deepen cynicism and reinforce the belief that minerals serve the few while burdens fall on the many.

The choice before us is not between order and chaos, or between investment and transparency. It is between constitutional governance and expedient control. Our Constitution has already made that choice. The question is whether we are prepared to honour it.