Zambia needs more than politics to prosper

The moral compass of civic and faith leadership

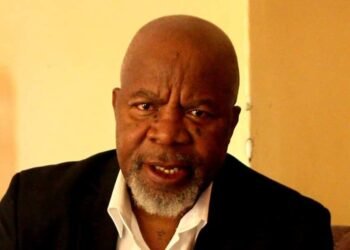

By Elvis Ng’andwe

ZAMBIA stands at a critical juncture. We are blessed with brilliant citizens, gifted academics, skilled professionals and creative innovators whose talents could transform our nation. Yet, paradoxically, many of these capable Zambians deliberately avoid politics. The reason is simple but tragic: our political culture has become too toxic, vindictive and personal. To enter politics is often to risk one’s peace of mind, reputation and dignity.

When popularity Trumps competence: Here lies the heart of Zambia’s dilemma. Politicians are not required to prove competence before assuming office. They take no examinations in law, economics or governance. They simply win elections, most often through charisma, connections or populism. Meanwhile, the people with the knowledge to design better systems of governance remain spectators, their expertise untapped.

Across our universities, hospitals, law firms, farms and factories, Zambia’s best minds are hard at work, but few have a voice in shaping public policy. Their ideas could strengthen the economy, reform the education sector and improve health systems, yet they remain sidelined by partisan politics. We must therefore ask ourselves; “must politics remain the only gateway to serving one’s country?”

Learning from other regions: Elsewhere, societies have found ways to bridge this gap. In Europe, independent experts and civil society are integral to governance. The European Union (EU) transparently consults think tanks, professional associations and universities when designing policies on trade, migration, and climate change. In North America, civic movements spearheaded monumental reforms, from environmental protection to civil rights.

Zambia, too, has seen the positive influence of non-partisan institutions, for instance, The Jesuit Centre for Theological Reflection (JCTR) and other CSOs have since long shaped national dialogue on the cost of living and social protection.

The lesson is clear: when civil society, academia and professional associations are given space, democracy is enriched and governance becomes more responsive. Rather than viewing these institutions as adversaries, government should treat them as partners, “good Samaritans” offering evidence-based reality checks that strengthen policy and protect the national interest.

Faith and democracy – The Catholic Church’s enduring witness: This partnership between civic competence and moral conscience is nowhere more evident than in the Catholic Church’s role in Zambia’s democratic journey. In the Jubilee Year of Hope 2025, the Church’s message of renewal and justice resonates powerfully in a nation still striving for integrity and inclusivity.

From the 1990 pastoral letter ‘The Nation We Want’ to its present-day advocacy, the Catholic Church has consistently stood as a guardian of the Constitution and a defender of dignity. That 1990 letter was more than a statement of faith, it was a moral awakening that helped usher in Zambia’s democratic transition.

A decade later, when President Frederick Chiluba sought an unconstitutional third term, the Church again raised its prophetic voice, calling the move a “betrayal of the people’s trust”. The alliance that followed between the Church, civil society and citizens preserved Zambia’s young democracy.

More recently, the church joined other faith-based and civic actors to oppose “Bill 10,” warning that the Constitution is a social covenant, not a partisan tool. Today, as “Bill 7” and the so-called Technical Committee on Constitutional Reforms emerge, the same vigilance remains essential. A constitution drafted in secrecy, without broad consultation, risks becoming a political weapon rather than a people’s charter.

The theology of public responsibility: The Church’s involvement in public affairs is not political opportunism but theological obligation. Catholic Social Teaching, from Pacem in Terris to Fratelli Tutti, reminds us that faith without social responsibility is empty. The church does not take sides; it takes a stand, for justice, human dignity, and peace.

Its engagement through pastoral letters, civic education, mediation, and election observation is part of its prophetic citizenship. By doing so, it calls both leaders and citizens to moral accountability. The church’s voice is not against government; it is against injustice. It is not anti-development; it seeks authentic development rooted in human dignity and solidarity.

Bill 7 and the question of legitimacy: The ongoing debate over Bill 7 reflects a deeper concern about legitimacy in governance. The so-called Technical Committee drafting constitutional changes lacks a clear mandate from the people. By operating behind closed doors and excluding key stakeholders, including churches, legal experts, and civil society, it undermines both the spirit and letter of constitutional democracy.

Reforms imposed through secrecy risk eroding public trust. Genuine constitutional reform must be transparent, inclusive, and nationally owned. Anything less is constitutional capture disguised as consultation. As the Church rightly insists, the Constitution belongs to the people, not to any government of the day.

Collaboration across faiths and sectors: Throughout Zambia’s democratic history, moral leadership has not been confined to one denomination. The Oasis Forum, bringing together the Zambia Conference of Catholic Bishops (ZCCB), the Council of Churches in Zambia (CCZ), the Evangelical Fellowship of Zambia (EFZ), and the Law Association of Zambia (LAZ), remains a model of interfaith collaboration. Together, these institutions have defended the Constitution, resisted manipulation, and upheld justice.

Faith-based research institutions such as JCTR continue to bridge theology and public policy, grounding advocacy in data and moral reflection. By analysing poverty trends, taxation, and public spending, they remind the nation that governance must always serve the common good.

Beyond politics – the ballot, the brain and the conscience: Zambia’s progress requires a deeper rethinking of governance. The ballot remains essential, but it is not enough. True development demands the active participation of professionals, academics, and moral leaders in shaping national policy. We must institutionalise expert councils where engineers advise on infrastructure, doctors shape healthcare systems, and economists guide fiscal discipline, without fear of political retaliation.

Politics should not monopolise public service. Our brightest minds should not be forced to choose between silence and partisanship. They deserve structured platforms to serve their country with integrity.

A call to moral courage: The Catholic Church’s consistency through successive regimes, UNIP, MMD, PF, and now UPND, demonstrates that moral courage does not shift with political winds. The Church supported democratic change when the UPND was in opposition; it now holds the same government to the same standards it once demanded of others. To mistake accountability for hostility is to forget history.

Prophetic voices have always carried a cost. Priests have been insulted, bishops threatened, and churches vilified for speaking truth to power. Yet silence in the face of injustice is not neutrality; it is complicity. As history teaches, societies that suppress conscience ultimately decay from within.

Conclusion–Building a Zambia Beyond Politics: If Zambia is to prosper, it must move beyond politics as a zero-sum contest for power. We need a governance culture that respects knowledge, honours conscience, and welcomes moral critique. The Church and civil society must be recognised not as obstacles, but as partners in building a just and prosperous nation.

The future we seek will not come from political slogans or partisan victories. It will come from the collective wisdom of the ballot, the brain, and the conscience, from citizens and institutions that love Zambia enough to tell her the truth.

Zambia’s tomorrow depends on whether we can listen to such voices today.

Elvis Ng’andwe is a Zambian lawyer and member of the Congregation of the Missionaries of Africa, currently Executive Secretary at Africa-Europe Faith & Justice Network (AEFJN) Brussels-Belgium.