“WE ARE NOT FREE ANYMORE” – ZAMBIA CRIES FOR INDEPENDENCE 2.0

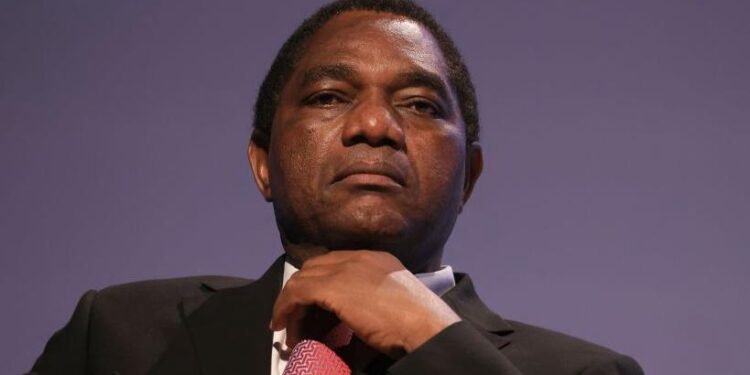

From colonial chains to Hakainde’s gagging, we are moving in circles.

By Thandiwe Ketiš Ngoma

Independence is not a date. It is a destiny of freedom.

Zambia’s story is one of courage, resilience and hope. From the chains of colonial rule to the dawn of freedom in 1964, Zambians have always yearned for liberty. Not only political, but economic, social and spiritual. Today, as the nation stands at a crossroads, the call for a Second Independence echoes through the nation. This is not a rebellion. It is a rebirth.

Let us take a walk down memory lane and observe why our forefathers fought for independence. Under British colonial rule, Northern Rhodesia lived under the heavy hand of racial segregation. In housing, education and employment, the colour of one’s skin determined one’s worth. Indigenous people dug copper from the earth but never owned the mines. They paid high taxes yet had no say in governance.

When the Central African Federation was imposed in 1953, the fear of permanent white rule spread like a fever. From that fear rose nationalist movements, the ANC under Harry Mwaanga Nkumbula, the ZANC under Kenneth Kaunda, and later UNIP, all united by a single cry for self-rule and dignity. They fought for equality, for access to education, for fair pay and for the right to speak. After years of arrests, protests and blood, the dream was born. On 24 October 1964, under a sky bright with promise, Zambia stood tall and free.

In those first years, hope filled the air. Schools multiplied. From barely 2,500 Africans in secondary education in 1960, there were over 54,000 by 1971. The University of Zambia opened its doors in 1965. The young state reclaimed mineral rights, built roads, hospitals and schools, and invested in health, transport and communication. Zambia became a fortress of liberation, giving sanctuary to freedom fighters from Namibia, Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and South Africa. The dream seemed complete, and for a moment, the nation truly believed it had arrived.

Then slowly, almost quietly, that freedom began to fade. Kenneth Kaunda, the founding father, believed unity required a single voice. By 1973 he had declared Zambia a One-Party State, arguing that it would have been disastrous for Zambia to go multiparty. In seeking unity, he suffocated diversity. Newspapers were tamed, opposition was banned, and those who questioned authority were imprisoned. What had begun as liberation turned into obedience.

By the early 1980s, the copper price collapsed, and the economy along with it. Queues for sugar and cooking oil grew longer as the speeches grew louder. Discontent simmered until, in 1991, the people again demanded change. Out of that cry rose the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy. Frederick Chiluba, a trade unionist with polished shoes and promises of renewal, became president. He stood before the nation and declared, “The hour has come.” Zambia believed him.

But in 1996 he amended the Constitution to bar Kaunda from contesting elections. The same document that had given hope was now used to silence an opponent. The pattern was repeating itself, preaching the power of democracy while practicing exclusion.

When Levy Mwanawasa took office in 2002, he came with a lawyer’s precision and a reformer’s heart. He fought corruption and brought a measure of order, but when his constitutional plans faced resistance, he called his critics traitors. Once again, the voice of authority disguised itself as law.

Rupiah Banda, who followed him, was different. Gentler, reflective. Handing power to Michael Sata, he reminded the nation, “Power is not forever.” It was a lesson few took to heart.

Sata, fiery and fearless, spoke for the working class and for the poor. He declared that a good Constitution is the one that stands against the president himself. Those words captured the essence of what Zambia had lost, a system strong enough to protect citizens even from their rulers. Yet fate cut him short before he could finish what he started.

After Sata’s death, Edgar Lungu took the mantle and, in 2016, signed the Constitution Amendment Bill at Heroes Stadium, calling it a people’s Constitution. The people cheered, but the concentration of power never truly shifted. To this very day, the presidency remained the sun around which every institution revolved.

Now, under Hakainde Hichilema, the circle tightens again. Bill 7 seeks to expand Parliament and alter electoral rules, moves critics fear will entrench executive control. Bill 13, the Lands and Deeds Amendment, allows the Chief Registrar to cancel land titles without judicial oversight. For farmers, investors and families who worked their land for generations, it feels like history repeating itself, a quiet return to colonial dispossession under local hands.

Even the digital age has not spared the spirit of control. Before independence, colonial rulers arrested Africans for agitating against the Crown. Today, citizens are charged with defaming the President. Only this week, the Patriotic Front and Tonse Alliance Secretary General Raphael Nakachinda was sent to jail for “defaming the President.”

The new cyber laws criminalise false information, a term so vague it can mean anything the government wants it to. Phones are tapped, journalists harassed, and online dissent punished. From colonial decrees before 1964 to modern surveillance in Hichilema’s regime, the script remains the same: silence the citizen, protect the throne.

And so the call for a Second Independence grows louder with every passing day. It is not a call to arms but a call to conscience. It comes from the farmer who fears losing his land, from the student who cannot find work, from the journalist threatened for speaking the truth, from the opposition member banned from assembling, and from every Zambian who feels democracy slipping through their fingers. This movement does not seek to destroy. It seeks to restore.

True independence must go beyond flags and anthems. It must mean economic sovereignty where Zambians own their copper, their farms and their industries. It must mean energy self-reliance, no child studying by candlelight in a country blessed with rivers and sun. It must mean justice, where courts answer to the Constitution, not to the President. It must mean freedom of speech, not as permission to praise but as the right to question.

History has already left us its lessons. Kaunda taught that Africa must be free. Chiluba said, “The hour has come.” Mwanawasa warned that corruption is treason against the people. Banda reminded us that power is temporary. Sata urged that a good Constitution must restrain even the president. Lungu set a people’s Constitution in motion. And now the people themselves must finish it.

Zambia has had independence for sixty-one years, yet her people still plead for the very freedoms their fathers fought to secure. Independence without justice is theatre. Independence without equality is illusion. If 1964 gave us a flag, then 2025 must give us a voice. If the first independence freed our bodies, the second must free our minds and our institutions.

The time has come to stop marking independence by fireworks and start measuring it by freedom. The next liberation must be constitutional, economic and moral, a people’s awakening where every citizen becomes the custodian of the Republic.

Independence is not a date. It is a destiny. And that destiny is ours to claim once again.