Selective justice is injustice: Why Zambia’s

anti-corruption crusade rings hollow

“You cannot fight corruption by hiding the corrupt”

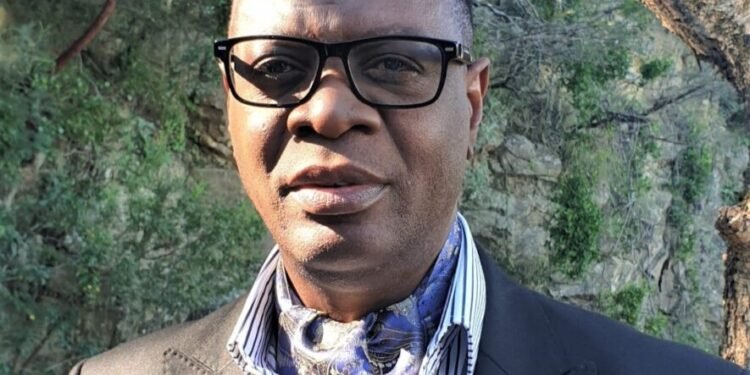

By

Prof. Cephas Lumina

ON A recent visit to Lusaka, I noticed large billboards featuring President Hakainde Hichilema accompanied by a bold call to action: “Say No to Corruption. Stand with the President. Fight Corruption. Save Zambia.” These statements, impossible to overlook for their prominence across the capital and moral gravity, reflect the President’s commitment to eliminating graft in public institutions.

As someone committed to governance, accountability, transparency, and reform, I took that message seriously. This piece is my response to the President’s call, and my modest contribution to what must be a collective national effort to reclaim integrity. But to fight corruption, we must confront uncomfortable truths. The anti-corruption campaign in Zambia is faltering. The very institution at its heart—the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC)—is losing credibility.

What is emerging is not a campaign grounded in justice or the rule of law. Instead, it shows political selectivity, institutional interference, and silence. The recent “redeployment” of Monica Mwansa, the ACC’s former Deputy Director-General, shows how internal integrity is undermined by political interests. Mwansa was known as a professional and independent career officer. Her unexplained removal was widely seen as a move to prevent her from doing her job, especially if it threatened those in power.

If Zambia’s anti-corruption crusade is to be taken seriously, it must begin by fixing the very institutions meant to lead it. The ACC cannot be both a political tool and an anti-corruption watchdog. It cannot call for accountability on one side of the political aisle while shielding those on the other. And it certainly cannot maintain public trust if it refuses to disclose the truth, especially about those in power. These concerns point directly to cracks in the ACC’s anti-corruption drive.

The cracks in the ACC’s anti-corruption drive

When President Hichilema took office in August 2021, he promised accountability. Anti-corruption was to be a focal point of his administration. He pledged a “zero-tolerance policy” on corruption. He promised the fight would be “professional and not vindictive,” and that institutions would be given “unfettered autonomy to… carry out their mandate without fear or favour.” At the launch of the National Policy on Anti-Corruption in May 2024, he stated that the government was fighting “past, present, and future corruption.” He underscored the need for the nation to “join hands and fight corruption, regardless of who is involved.”

Since August 2021, a series of high-profile investigations and asset seizures has been conducted, primarily targeting officials from the previous Patriotic Front (PF) administration. Several former ministers and party officials were publicly named, arrested, and prosecuted. These actions were initially welcomed by many citizens and observers who had long grown weary of impunity.

However, over time, the fight against corruption began to appear less like a national cleansing and more like selective retribution. Credible allegations and murmurs involving the current administration surfaced, but the ACC’s appetite for action diminished. Whispers of procurement fraud, unexplained wealth, or abuse of office by sitting government officials have not been met with arrests or inquiries. Instead, the ACC now says it will not name senior officials under investigation (Angela Muchinshi, “We can’t name ministers being investigated, that’d be unprofessional – ACC,” News Diggers, 30 July 2024).

This sets a dangerous precedent. Shielding the identities of high-ranking individuals under investigation undermines public trust and fosters a culture of impunity. This is not a call for a trial by media; it is a statement that transparency and accountability are essential to democratic governance.

The ACC’s position raises several questions: Who decides which names are too sensitive to disclose? On what legal basis is the information withheld? How does the public distinguish between genuine investigations and political cover-ups?

A core tenet of democratic accountability is that public officials, especially those entrusted with power and public resources, are subject to public scrutiny. It is also worth noting that the Anti-Corruption Act, 3 of 2012 provides for “the prevention, detection, investigation, prosecution and punishment of corrupt practices and related offences based on the rule of law, integrity, transparency, accountability …” (emphasis added).

The ACC’s decision to withhold names of senior officials under investigation demonstrates that the institution prioritizes political sensitivities over democratic accountability.

The myth of “confidential investigations”

The ACC’s argument for withholding names under investigation relies on procedural confidentiality. While confidentiality is important early on to prevent reputational harm from unfounded accusations, it should not be used to protect political elites indefinitely.

In cases involving high-level public officials and significant public interest, the threshold for disclosure must be lower. Investigative bodies worldwide routinely issue statements when politically exposed persons are under formal investigation. This does not equate to guilt; it ensures democratic accountability. Once investigations reach a certain stage, such as when the subject has been formally interviewed or evidence gathered, disclosure serves the public good by deterring obstruction, fostering civic oversight, and reinforcing trust in institutions.

Shielding the powerful under the guise of due process creates a double standard. Former government and ruling officials and lower-ranking civil servants are often publicly named during investigations. Why not ministers? Why not ruling party members? The ACC’s silence disproportionately protects those with power, which is the opposite of what an anti-corruption commission should do.

These challenges are illustrated by the recent “Monica Mwansa moment,” which raises questions about whether her redeployment was simply routine or a cover up.

The “redeployment” of former ACC Deputy Director-General Monica Mwansa must be understood in this context. Mwansa was considered a decisive official who upheld the ACC’s mandate regardless of whose interests were involved. Her “redeployment” occurred without explanation. It was abrupt, opaque, and appeared politically motivated.

Whether or not Mwansa was probing too close to the political elite is a matter of speculation—but the silence surrounding her “redeployment” speaks volumes. If ACC leadership can be reshuffled or punished for doing their job too well, what message does this send to the remaining officers? To whistleblowers? To the public?

The message is unmistakable: the fight against corruption is permissible—provided it does not threaten political interests.

Why the ACC is falling short

The ACC is constitutionally enjoined to be subject only to the Constitution and the law; be independent and not subject to the control of a person or authority in the performance of its functions; act with dignity, professionalism, propriety, and integrity; be non-partisan; and impartial in the exercise of its functions.

Nevertheless, the ACC suffers from deep-rooted structural and political weaknesses. These conflict with its constitutional principles. First, the ACC is structurally tied to the Executive. Its legal mandate is broad, but it lacks insulation from the Executive. The President appoints ACC Board members and the Director-General. Parliament must approve appointments, but removal does not require much parliamentary scrutiny. This creates an incentive for the ACC to protect political interests rather than pursue justice and erodes the ACC’s effectiveness and public trust. Second, the ACC’s budget is subject to government approval, making it vulnerable to pressure. Third, there is little public visibility into how cases are prioritized or dropped. The refusal to disclose names further erodes public confidence. Fourth, while several institutions oversee the ACC, its independence is in question. There is political interference and internal issues. Balancing independence with reporting to the executive and legislature is a key problem. The removal of the board in July 2024 highlighted these vulnerabilities. Fifth, high-profile cases involving ruling party allies often stall. Past cases become political tools while new ones remain buried. Without impartiality and transparency, enforcement lacks legitimacy. Sixth, investigations often drag on. Evidence leaks and prosecutions collapse, sometimes for procedural reasons, but often due to interference. Public confidence fades when ACC’s announcements do not result in convictions.

Learning from global best practices

The ACC can learn much from international best practices, particularly those of Hong Kong’s Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) and Singapore’s Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB), both widely regarded as models of institutional integrity, effectiveness, and independence.

Hong Kong’s ICAC, which was established in 1974, operates on three fronts: investigation, prevention, and education. Its credibility stems from complete operational independence, insulation from political interference, and strong internal accountability. Its Commissioner is appointed by the Chief Executive (akin to a president or prime minister), but critically, under the Basic Law, the ICAC enjoys strong protections: fixed enrichments of budget, independent prosecutions, and a professionalized, rule‑bound operational structure. While political headwinds exist, the institution has carved out a powerful independent niche.

The ICAC routinely publishes reports, names individuals under investigation once probable cause is established, and has strict internal mechanisms to avoid political bias. It routinely investigates both senior and junior officials and makes key findings public—balancing legal fairness with public transparency. It commands public trust because it acts—visibly, consistently, and impartially.

Singapore’s CPIB operates under the Prime Minister’s Office, but with statutory safeguards that guarantee operational autonomy. It is empowered to investigate anyone, including ministers and senior civil servants. Singaporean leaders have themselves been subject to investigation, reinforcing the principle that no one is above the law. The CPIB is feared, respected, and effective because no one is seen as untouchable.

The key to both models? Impartiality, institutional independence, and transparent communication. These are precisely the qualities the ACC currently lacks.

Reform or ruin: The path forward

The fight against corruption must be more than a political weapon or public relations exercise. It must be rooted in impartiality, transparency, and institutional strength. The ACC, in its current form, has demonstrated its inability to deliver on that promise.

To restore credibility and align with constitutional principles, Zambia’s anti-corruption framework needs reform. The ACC must be reimagined, not just strengthened. Here are some actionable recommendations. First, the ACC leadership should be appointed through a bipartisan parliamentary process, not at the President’s discretion. Removal should require a two-thirds parliamentary vote on defined grounds such as serious misconduct or incapacity. This is the only way to build lasting public confidence. Second, ACC funding should be protected by law and allocated directly by Parliament. This would reduce Executive financial leverage. Third, the ACC should report to Parliament, not the Executive. Fourth, the ACC must disclose when it begins investigations into constitutional office holders or cabinet-level officials. This ensures transparency without presuming guilt. The Commission can develop a framework to disclose when a case passes preliminary review or involves public funds above a set amount. Fifth, a non-partisan Public Integrity Advisory Board should be established to review high-profile cases, oversee case closures, and publish transparency reports. Sixth, a Whistleblower Protection Act should be enacted to guarantee anonymity, immunity, and security for whistleblowers and investigators. Seventh, anti-corruption education at schools and community level should be institutionalized, as ICAC in Hong Kong has done. Eighth, officials like Monica Mwansa must be protected, not purged.

Conclusion: The President’s call must be met with courage

President Hichilema’s call to “join him in the fight against corruption” is one that many Zambians, myself included, are ready to answer. But joining the fight does not mean cheering from the sidelines. It means demanding that the institutions entrusted with justice are truly independent, impartial, and accountable.

The fight against corruption cannot be won with billboards, press conferences, or selective prosecutions. It will only be won when truth is pursued without fear or favour, when whistleblowers are protected, not punished, when dedicated ACC officials are not purged, and when institutions like the ACC serve the people, not political interests.

Until that day comes, the anti-corruption campaign risks becoming a cover for impunity dressed up as justice, punishing yesterday’s enemies while protecting today’s allies.