Defending the Judiciary: Why the attacks on Chief Justice Mumba Malila miss the mark

By

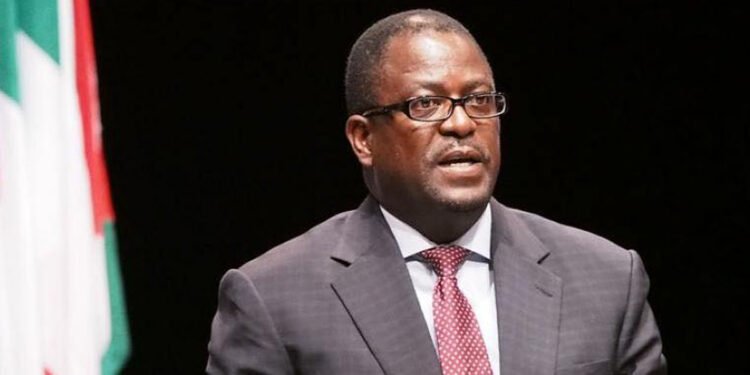

CHIEF Justice Dr Mumba Malila, SC has recently faced mounting political criticism. He has been accused of allowing the Executive to “capture” the Judiciary, of failing to defend judicial independence, and of neglecting to discipline errant judges and magistrates. Some critics have gone further, petitioning regional bodies and alleging that under his leadership the courts are aligned with the Executive and hostile to the opposition.

These are grave allegations. They go to the heart of constitutional governance and public confidence in the rule of law. But they rest on a misunderstanding of Zambia’s constitutional architecture — particularly the principles of separation of powers and judicial independence. Where weaknesses exist within our justice system, they are structural and systemic. They are not the result of personal abdication.

If we are serious about defending judicial independence, we must begin with first principles.

Separation of powers in our constitutional order

Separation of powers is a constitutional safeguard against the concentration of state authority in a single institution or individual. In Zambia, power is divided among three co-equal branches of government — the Legislature, the Executive, and the Judiciary — each with defined constitutional functions and each tasked with checking the others.

Article 119 of the Constitution vests judicial authority in the courts and requires that it “be exercised in accordance with (the) Constitution and other laws.” Articles 122 and 123 guarantee judicial independence, including administrative and financial autonomy. Article 122(2) expressly prohibits any person or authority from interfering with judicial functions.

But separation does not mean isolation. Parliament enacts laws. The Executive implements them. The Judiciary interprets and applies them, ensuring that both Parliament and the Executive act within constitutional limits. When courts invalidate legislation, they are not “attacking” Parliament; they are performing their constitutional duty. When they review executive action, they are not undermining government; they are upholding the rule of law.

Equally important is what courts do not do. Judges do not allocate national budgets. They do not initiate prosecutions. They do not design or implement public policy. They adjudicate disputes brought before them.

If funds appropriated to the Judiciary are not released on time, that is an executive act. If Parliament fails to enact legislation securing the Judiciary’s full financial autonomy, that is a legislative omission. It is neither legally nor logically coherent to attribute such failures to the Chief Justice.

The Constitution deliberately disperses authority. Judges are appointed by the President on the recommendation of the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) and subject to ratification by the National Assembly, while all other judicial appointments are made through processes involving the JSC. Budgetary allocations are determined through national fiscal processes led by the Executive and approved by the Legislature, processes in which the Judiciary does not meaningfully participate. Disciplinary mechanisms are governed by statutory bodies. Case allocation operates at court level. These arrangements are safeguards against the centralisation of power.

Restraint within this framework is not weakness. It is constitutional discipline.

Judicial independence: What it means — and what it does not

Much of the criticism directed at Chief Justice Malila reflects a superficial invocation of “judicial independence” without appreciating its complexity. That independence operates at two interconnected levels: institutional and personal.

Institutional independence concerns the autonomy of the Judiciary as a branch of government — its structural, administrative, and financial independence. Our Constitution recognizes this clearly. Article 123 declares the Judiciary a self-accounting institution entitled to adequate funding. Judges enjoy security of tenure until retirement age, and their offices cannot be abolished while there is a substantive holder. At common law, judicial immunity protects judges from civil liability for acts performed in good faith in the discharge of their functions. These safeguards insulate judges from political retaliation or inducement.

Yet, constitutional guarantees must be implemented in practice. In Sangwa v Attorney-General (31 July 2023), the Constitutional Court held that financial independence is “cardinal” to judicial independence and found that Parliament and the Minister of Finance were in breach of the Constitution for failing to enact legislation securing full financial autonomy of the judiciary. The Court endorsed the World Bank’s 2022 Zambia Judicial Sector: Public Expenditure and Institutional Review, which recommended guaranteeing the Judiciary an adequate and predictable share of the national budget. It ordered the Minister to report to Parliament every six months on measures taken by the Executive to secure financial independence and adequate funding for the Judiciary until the required legislation and measures were in place. It does not appear that this order has been complied with.

That judgment recognized systemic deficiency, not personal failure.

When infrastructure projects stall because funds are delayed, when newly appointed judges lack official vehicles to manage circuits effectively, and when judges are compelled to share offices and courtrooms, the consequences are tangible: postponed hearings, delayed judgments, and mounting case backlogs. These inefficiencies flow from resource constraints. They are not evidence of executive “capture” or “failure” by the Chief Justice.

As the Sangwa case shows, financial autonomy requires legislative reform and executive compliance. It cannot be achieved by administrative will alone.

Personal independence — often described as decisional independence — protects individual judges in the exercise of adjudicative power. Judges must decide cases based on law and evidence, free from improper influence from any quarter, including from within the Judiciary itself — either from the Chief Justice or other judges.

Reports that some members of the public have written to the Chief Justice urging intervention in pending High Court matters involving the Patriotic Front (PF) betray a misunderstanding of constitutional design. The Chief Justice cannot direct a judge on how to decide a case, withdraw a politically sensitive matter, substitute his judgment for that of a trial judge, or take over a case properly allocated to another judge. To do so would violate decisional independence.

The remedy for delay lies in established procedural mechanisms. The remedy for legal error is appeal. The remedy for misconduct lies in the statutory disciplinary framework.

Judicial independence protects litigants from decisions shaped by politics, power, money, fear, or improper pressure, ensuring that cases are resolved according to law. It also protects judges from hierarchical command and external influence.

Case allocation: A safeguard against centralised control

Allegations of manipulation or failure to supervise sometimes extend to case allocation. Yet section 21 of the Judiciary Administration Act, 23 of 2016, provides that each court has a judge or judicial officer, designated by the Chief Justice, who is responsible for allocating cases within that court. The Chief Justice designates the allocating officer; he does not assign individual cases. This decentralised allocation model exists precisely to prevent interference and to safeguard fairness and decisional independence.

Claims that he manipulates case assignment or that he has failed to properly “police” judges and magistrates in this context are inconsistent with the statutory framework.

The limits of the Chief Justice’s authority

The misconception that the Chief Justice participates in case allocation reflects a broader misunderstanding of his constitutional role. Public discourse often assumes that he exercises sweeping and unilateral authority over the entire judicial system. That perception is constitutionally inaccurate. Our legal framework deliberately disperses authority to prevent the concentration of power in a single individual — including the head of the Judiciary.

Article 136(2) of the Constitution provides that the Chief Justice is responsible for the administration of the Judiciary and must ensure that judges and judicial officers perform their functions “with dignity, propriety, and integrity” and “without fear, favour or bias.” Some critics interpret this as conferring sweeping disciplinary powers. It does not. The provision imposes leadership responsibility, but it does not vest the Chief Justice with unilateral authority to discipline, suspend, or remove judges.

Disciplinary processes are governed by distinct constitutional and statutory mechanisms. The JSC exercises disciplinary control over judicial officers appointed under the Judiciary Administration Act. Complaints against superior court judges (including the Chief Justice) are handled through the Judicial Complaints Commission (JCC) under the Judicial (Code of Conduct) Act, 13 of 1999, and may culminate in tribunal proceedings and removal by the President. The Chief Justice may refer matters within this framework, but investigations and sanctions proceed according to procedures designed to protect due process and decisional independence.

A similar misunderstanding arises in relation to appointments. The Chief Justice has no role in the judicial appointments process. As stated earlier, appointments are conducted through the JSC. The Chief Justice is not a member of the JSC and does not participate in shortlisting. Responsibility for the quality of appointments therefore lies within that institutional framework.

Concentrating appointment or disciplinary authority in the office of the Chief Justice would undermine the very independence critics claim to defend. Conversely, weaknesses in those systems cannot be remedied by expecting the Chief Justice to exceed powers he does not possess.

Even administratively, the Chief Justice’s authority is not unfettered. He cannot compel the release of appropriated funds, unilaterally expand the judiciary’s budget, or implement structural reforms without resources approved through executive and legislative processes.

He is the administrative head of the Judiciary. He is not its command centre.

Public perception, integrity, and reform

Public concern about judicial corruption has long unsettled the country. Surveys by Transparency International have reflected anxieties about integrity within parts of the justice sector. Perception matters. It shapes institutional legitimacy and public trust.

Under Chief Justice Malila’s tenure, there has been renewed emphasis on oversight and transparency, particularly in the lower courts. The introduction of livestreaming rules has expanded public access and reinforced openness. These measures do not resolve every concern, but they signal institutional reform rather than concealment or failure.

Chief Justice Malila’s professional record long predates his appointment to the Bench. He has served as Attorney-General of Zambia, Chairperson of the Human Rights Commission, a member of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and, currently, as a member of the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention.

Having served two terms as a UN Human Rights Council “special procedures” mandate holder and now a second term on the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, I am familiar with the rigorous scrutiny accompanying appointments to UN human rights mechanisms. Such roles demand demonstrable independence and integrity. I also know that Chief Justice Malila is highly respected within the UN and regional human rights systems.

It is implausible that a jurist with such a distinguished record would suddenly abandon those commitments. Criticism of institutional performance should be grounded in structural analysis, not conjecture about personal integrity.

Addressing inefficiency in the judiciary: A constructive proposal

Defending the Judiciary does not mean ignoring legitimate concerns about inefficiency. Delayed judgments and case backlogs erode public confidence in the administration of justice and must be addressed.

Section 4(1) of the Judiciary Administration Act empowers the Chief Justice to establish advisory committees on matters relating to the administration of justice. The establishment of a Judicial Administration Review Committee under this provision would, in my view, be a constructive step. Its mandate could include investigating causes of delayed judgments, examining structural bottlenecks, reviewing allocation systems, assessing infrastructure, and staffing constraints, and proposing reforms consistent with judicial independence.

Regional practice supports this approach. Kenya and South Africa have successfully implemented efficiency reforms through statutory mechanisms while preserving decisional autonomy.

The real reform agenda

If we seek a stronger Judiciary, reform must be structural rather than personalised. The composition and transparency of the JSC should be revisited. Financial autonomy must be secured through legislation guaranteeing predictable and adequate funding. The disciplinary framework should be clarified and strengthened in a manner consistent with due process.

In a study I prepared for Chapter One Foundation titled The Balance of Justice: Evaluating the Frameworks for Judicial Independence, Integrity, and Accountability in Zambia (October 2024), I underscored that judicial independence cannot be divorced from integrity and accountability. Independence without transparent appointments risks public distrust. Accountability without safeguards risks political control. Our current framework — particularly the exclusion of the Chief Justice from the JSC and the diffuse disciplinary architecture — departs from regional best practice and warrants careful constitutional reconsideration.

Reform must therefore focus on recalibrating institutional design to strengthen both independence and accountability, rather than assigning personal blame for structural outcomes.

Conclusion: Structural reform, not personal blame

The rule of law does not survive on accusation. It survives on structure, restraint, and constitutional fidelity.

Chief Justice Malila operates within a constitutional framework that limits his authority over appointments, discipline, finances, and case allocation. Those limits are features of the country’s constitutional design — though the design itself is open to criticism.

In comparative perspective, Zambia’s framework is unusual. In most Eastern and Southern African countries, Chief Justices sit on — and often chair — their Judicial Service Commissions. In Zambia, the Chief Justice does not sit on the JSC, and his role in disciplinary matters is similarly circumscribed by statutory bodies over which he does not exercise decisive control.

These exclusions were intended to prevent concentration of power. Yet they also create structural gaps in leadership and accountability that do not fully align with regional best practice. A Chief Justice who is constitutionally excluded from the processes that determine who becomes a judge — and who faces discipline — cannot fairly be held personally responsible for systemic weaknesses arising from those processes.

If we are serious about strengthening judicial independence and public confidence, the answer lies in constitutional reform. The composition and procedures of the JSC require reconsideration. The balance between independence and accountability in disciplinary mechanisms must be reassessed. Financial autonomy must be entrenched in enforceable legislative guarantees. Structural deficiencies demand structural solutions.

To demand that the Chief Justice exceed his lawful authority to compensate for institutional design flaws is to invite constitutional overreach. The principled course is to confront those flaws directly, through transparent reform grounded in comparative best practice.

Judicial independence is preserved not by attacking the officeholder, but by building institutions that are structurally sound, accountable, and aligned with the standards to which the country has committed itself regionally and internationally.